I recently had the chance to do something that I’ve wanted to do for years: dump an arcade game to add it to MAME.

MAME is a massive emulator that covers thousands of arcade games across the history of gaming. It’s one of those projects I’ve used and loved for decades. I’ve always wanted to give back, but it never felt like I had something to contribute—until recently.

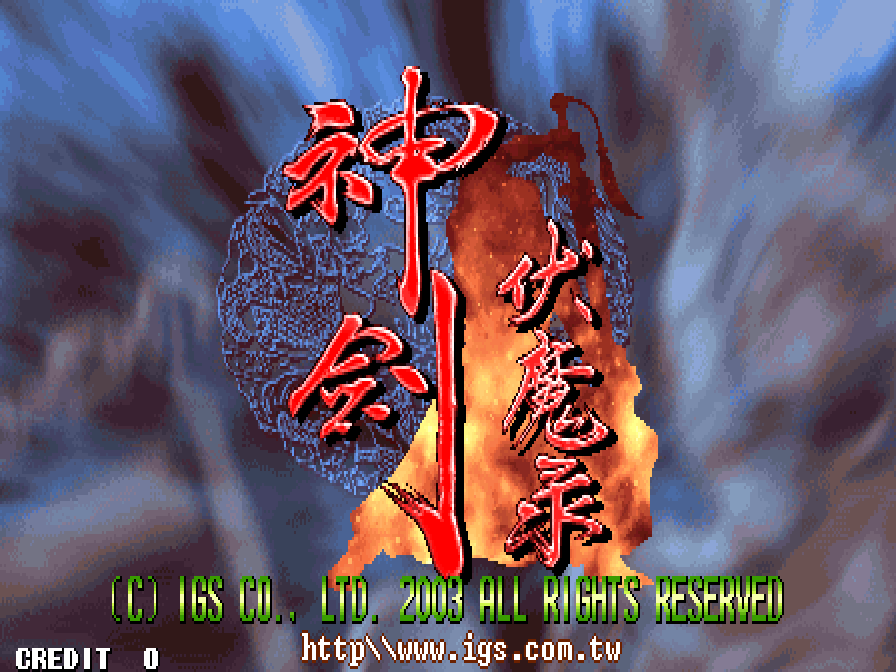

You might remember from one of my other posts that I recently got into collecting arcade games. This year I’ve been collecting games for a Taiwanese system called the PolyGame Master (PGM), a cartridge-based system with interchangeable games sold by International Games System (IGS) between 1997 and 2005. It has a lot of great games that aren’t very well-known, in particular some incredibly well-designed beat-em-ups.

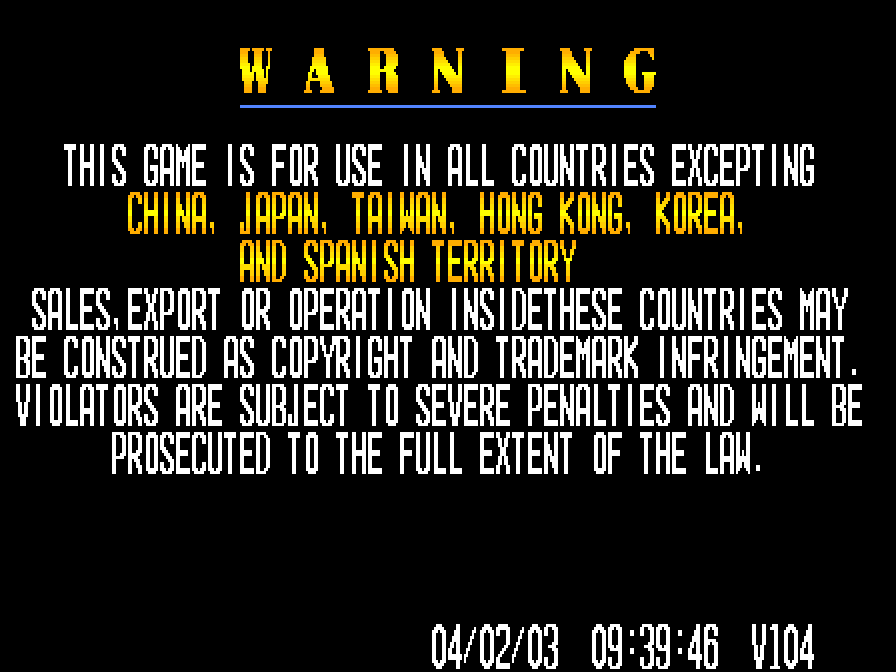

A couple months ago, I bought a copy of The Gladiator, a wuxia-themed beat em up set in the Song dynasty. My specific copy turns out to be an otherwise-undumped game revison. Many arcade games were released in many different versions, including regional variations and bugfix updates, and it can take collectors and MAME developers years to track them all down. In the case of The Gladiator, MAME has the final release, 1.07, and the first few revisions, but it’s missing most of the versions in between. When my copy came here, I booted it up and found out it was one of those versions MAME was missing: 1.04.

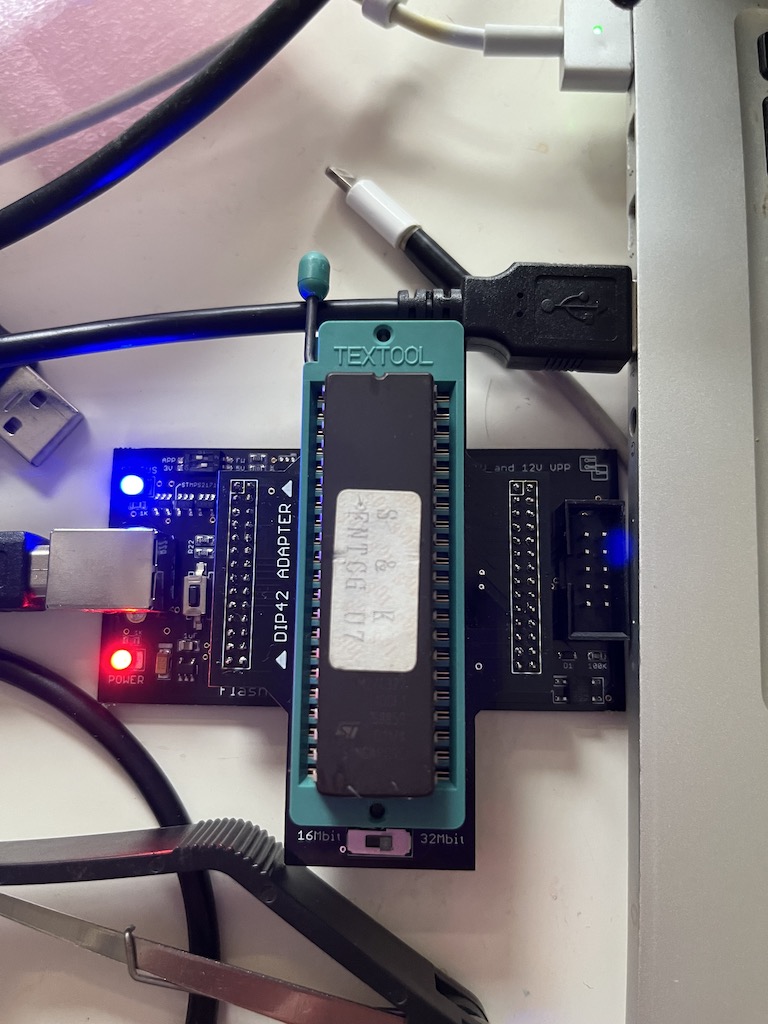

Luckily, I already had the hardware on hand to dump it. I own an EPROM burner that I’d bought to write chips so that I could mod games I’d bought, but EPROM burners can read chips as well. I own an adapter that supports several common chips that, luckily, can handle exactly the chips I needed for this game.

It’s easy to think of game cartridges as just being a single thing, but arcade game boards typically have a large number of chips. Why’s that? It’s partly technical; specific chips can be connected directly to particular regions of the system’s hardware, like graphics or sound, which means that even though it’s less flexible than an all-in-one ROM, it has some performance advantages too. The two chips I dumped here are program code for two different CPUs: one for the 68000 CPU in the system itself, and one for the ARM7 CPU in the game cartridge.

The other advantage is that using a large number of chips can make it easier to update a game down the line. Making an overseas release? It would be much cheaper to update just a couple of your chips instead of producing new revisions of everything on your board. Releasing a bugfix update? It’s much more quick and painless to update existing games if all your program code is on a single chip.

From looking at MAME, I could tell that every other revision of The Gladiator used a single set of chips for almost everything. Only the two program ROM chips are different between versions, which made my life a lot easier. I was also lucky that these chips were easy to get to. Depending on the kind of game, chips might be attached straight to the board, or they might be in sockets where they can be easily removed and reattached. The Gladiator has two game boards, one of which uses two socketed chips. And, thankfully, those were the only two chips I had to remove and dump.

To remove the chips, I used an EPROM removal tool—basically just a little set of pliers on a spring, with pair of needle noses that get in under the edge of the chip in the socket so you can pull it out. The two chips were both common types that my EPROM burner supports, so once I got them out they weren’t difficult to read. The most important chip, which has the game’s program code, is an EPROM chip known as the 27C160—a 2MB chip in a specific form factor. I already own a reader that supports that and the 4MB version of the same chip, which you can see in the above photo. The second chip is a 27C4096DC which has a much smaller 512KB capacity.

Why are there two program ROMs? Many games for the PGM use a fascinating and pretty intense form of copy protection. As I mentioned earlier, the PGM motherboard has a 20MHz 68000 processor, a 16-bit CPU that was very widely used in the 90s. The game cartridge, meanwhile, has a 20MHz ARM7 coprocessor. For early games, that ARM7 was there just for copy protection. Game cartridges would feature an unencrypted 68000 ROM and an encrypted ARM7 ROM; the ARM7 must successfully decrypt and execute code from the encrypted ROM for the main program code to be allowed to boot and run. By the end of the PGM’s life, they’d clearly realized it was silly to be devoting the ARM7 just to copy protection when it was faster than the CPU on the motherboard, so they put it to use for actual game logic. On games like The Gladiator, the unencrypted 68000 ROM and the main CPU are only doing very basic bootstrapping work and then hand off the rest of the work to the ARM7, which runs the game using code on the encrypted ARM7 chip.

I spent awhile fumbling around trying to get the dumped ARM7 ROM to work, but it turns out that’s because I read it as the wrong kind. Oops. My reader has a switch that switches between the 2MB and 4MB versions of the chip… and I had it set to 4MB, even though the chip helpfully told me right on the package it’s a 2MB chip. So, after I spent a half hour fumbling, I realize what I’d done and went back to redump it—and that version worked first try. Phew.

Once I dumped it, I was able to figure out that one of the two program ROMs is identical to one that’s already in MAME; only the ARM ROM is unique. That meant adding it to MAME was very easy; I could mostly copy and paste existing code defining the game cartridge, changing just one line with the new ROM and a few lines with some different metadata, and I was good to go. I submitted a pull request and, after some discussion, it was merged. For something I’ve wanted to be able to contribute to for years, feels good and, honestly pretty painless. And now, as of MAME 0.249, The Gladiator 1.04 can finally be emulated!